Remote conferences and seminars bypass the logistical, financial and environmental burdens of travelling. They can also encourage a greater diversity of participants, readily bringing together expertise and perspective from various career stages and backgrounds. However, virtual meetings are not without their drawbacks, especially when it comes to accessibility. Indeed, many of these problems have been highlighted as people turn away from the face-to-face format in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps with the current momentum of online platforms, now is the ideal time to address these issues and improve the accessibility of our online meetings for now and in the future. Here, we highlight some accessibility barriers that are often overlooked in online meetings and offer advice to organisers and presenters on how to mitigate these.

Making your presentations more accessible

In addition to general slide presentation, it is also important to consider the accessibility of your talk – is it suitable for a wide range of people, including those with impairments and disabilities such as poor vision, colour blindness, dyslexia and hearing problems? Below are some guidelines on how to make your virtual presentations more accessible:

1. Colour schemes: not all colours translate well onto slides. You want to use colours which are easy on the eye and contrast well. More importantly, do not rely on colours as the only method of distinguishing information – this is particularly important for those with colour-blindness. Instead, consider using the underline and bold functions.

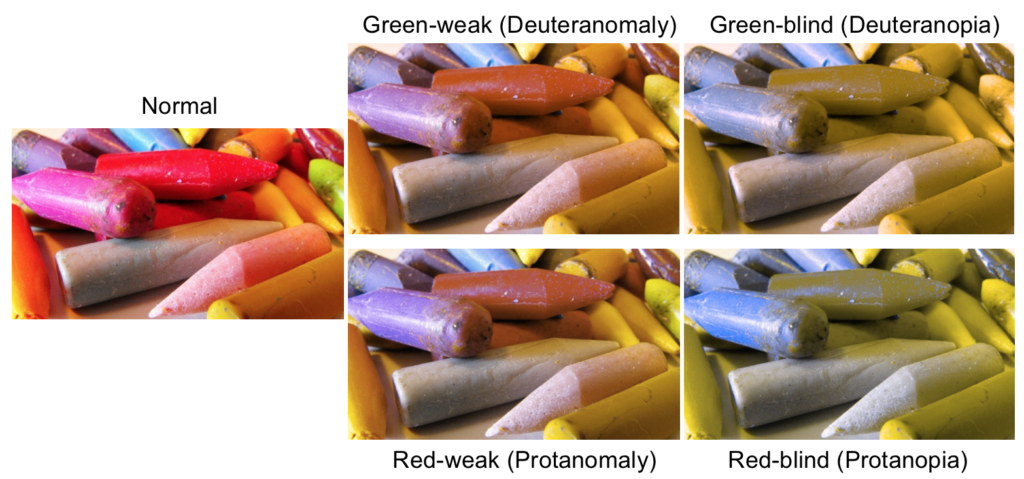

Depending on your computer system, you can also enable certain colour filters to your display which allow you to view your slides as someone with colour blindness may see them (red/green filter = protanopia, green/red filter = deuteranopia, blue/yellow filter = tritanopia and greyscale). With the current prevalence of deuteranomaly, there could be at least 1 individual in an audience of 20 (~6% for men and ~0.5% for women).

- On a Mac system you can access this function through System preferences –> Accessibility –> Display –> Colour filters.

- For windows systems select Start –> Settings –> Ease of access –> Colour filters.

- Scan through your slides in all these filters to check your colour scheme is suitable.

Alternatively, consider using websites, such as Coblis, which imitate how colour-blind individuals may see an image.

2. Font: Use a large and clear font. This is important to those with poor vision and for those with dyslexia. Stay clear of fancy/curly fonts, as these can be harder to read.

- Fonts such as Sans Serif, Arial, Helvetica, Calibri and Tahoma are considered suitable for most readers as the letters can appear less crowded.

- Recommended minimum font size is 14, but some dyslexic readers may require size 24.

3. Alternative Text: Include alternative text (alt text) for all visuals in your presentation. Alt text is a written copy that appears in place of/with a figure, which allows screen readers to provide a verbal summary of the figure to those with visual impairments. Adding alt text to visuals is often very simple and really helps engage people with visual impairments.

- When using programmes within the Microsoft Office suite, you can right click on a visual and select edit alt text. This brings up a box in which you can type 1-2 sentences to describe the figure to someone who cannot see it.

- Alternatively, you can click on an image and select Picture format –> Alt text

4. Layout: the layout of each slide and the presentation as a whole is very important in creating a presentation that is easy for all people to understand and follow.

- Provide a summary at the start of your presentation which outlines what you will discuss. This will give those who struggle to see the slides context for what they are hearing.

- Avoid walls of text – lots of text is a turn off, even for those without disabilities or impairment, however, large amounts of text is particularly troublesome to those with visual impairments.

- In addition to slide number, give each slide a unique title – this is helpful for audience members with poor vision or reading difficulties to recall what information is on which slide.

- Make sure the contents of your slide can be read in the order that you intend. When someone with good vision reads a slide, they tend to read things in the order the elements appear in the slide. However, a screen reader reads elements of a slide in the order they were added to the slide, which means people relying on screen readers may struggle to keep on track.

- Use pre-prepared slide layouts – PowerPoint contains built-in slide layouts that you can apply which automatically make sure that the reading order works for those using screen reader.

5. Check Accessibility: Use the “check accessibility” function within Microsoft Office applications to ensure that your slides are easy for people of all abilities to view and read. This function checks things like alt text, the order a screen reader reads the slide and errors in your tables or figures.

- To find this function, go to the Review tab and click the Check accessibility icon. This will generate a list of errors and warnings with how-to-fix recommendations for each issue.

Organising an accessible conference

Not everyone has access to the same technology and not everyone is digitally literate to use it intuitively. Moreover, accessing certain tools or content might not be possible for everyone. Therefore, the videoconferencing platform should be freely available to all conference attendees and should be compatible with assistive technologies (e.g. text-to-speech software, screen readers, magnification, braille display, etc). If assistive technology is not inherently part of the platform, alternatives should be planned ahead of time to ensure everyone has an enjoyable experience on their own terms. For instance, not all conference platforms have automatically-generated captions. This can be factored in the decision on which videoconferencing platform to use. Hiring real time translation interpreters is also an option that is highly recommended by the Special Interest Group on Accessibility and Computing (SIGACCES), along with sign language interpreters where applicable. There are also software tools which can transcribe ‘on the go’ e.g. Live Transcribe.

Unsure as to what accessibility features your conference will need?

Ask participants about accommodations or reasonable adjustments during registration, be it a food allergy or a Braille translation. Additionally, when providing adjustments make sure that all available accessibility features are well-documented and guide users as to how to set them up.

If the event went live on social media (e.g. Twitter), it might be a good idea to create a collection of tweets or a blog post summarising the tweets for those who were not on social media or for those who missed the event.

Creating a comfortable online meeting atmosphere

For some people, necessitating the use of camera during an online meeting can be exhausting, distracting and add pressure. To alleviate some of that stress, organisers should announce the general practice of presenters having cameras on, with the option to present without a camera.

Providing the slides ahead of time (with text descriptions of images) or pre-recording talks (with captions) permits people preparing ahead which could increase engagement. It might allow for thinking about that particular slide that caught your interest more critically. Furthermore, recording the meeting means it can be watched again and be correctly captioned.

Fostering diversity and creating an inclusive environment, asking attendees and presenters to share their pronouns at registration will aid in discussions later on and shows you support and respect people you interact with.

Different people work in different ways and it’s always a good idea to respect this diversity and taking it into account when planning an event. For instance, it’s fine to have an interactive session but there shouldn’t be pressure on people to participate when some would prefer to watch. Similarly, as people might have various obligations such as family commitments or emergencies to deal with, there is no need for a platform which displays the names of attendees joining or leaving.

If unsure how to approach making a conference accessible, why not ask for help from the community? Accessibility officers can be hired or feedback could be sought from disability communities (e.g. social media posts from disabled users indicating they have managed to use the software or posts proclaiming they are having difficulties in its operation). An important note here is to be open about trying to deliver an accessible virtual event and working together with the community to address any points raised.