Want a real life ‘Lessons in Chemistry’? Then this is the book for you!

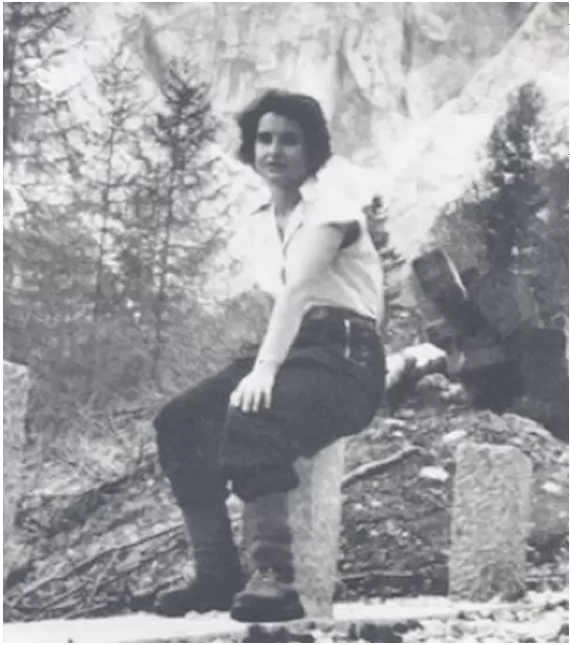

I’m going to be honest; I completely judged this book by its cover. A Rosalind Franklin biography written in 2002 with a classy sepia photograph on the cover did not seem like an exciting read to me. I began reading expecting a dry but informative account of Franklin’s scientific career that would do me good but would probably feel like a bit of a chore. Well, the famous idiom was right yet again, because from the first chapter of this book I was hooked. What this book actually is, is an incredibly moving and motivating account of an exceptional scientist’s battle to do her ground-breaking research in the face of sexism, antisemitism and the aftermath of WWII.

The story of Franklin’s life and career left me with a fire in my belly. Through the clever use of anecdotes and extracts from the copious letters Franklin wrote to friends and family throughout her life starting from boarding school at age 9, Maddox allows the reader to connect with Rosalind the person as we learn about Franklin the scientist. This strong understanding and empathy for Franklin as a tangible person makes the injustices she faced all the more infuriating.

Despite her fame in relation to the discovery of the structure of DNA, she spent the first decade of her research career, first in London and then in Paris (where she became fluent in French), investigating the structure of coal using X-ray diffraction and other techniques. It wasn’t until 1950 that she moved to King’s College London and began using X-ray diffraction to investigate the structure of DNA. There she used her knowledge of experimental X-ray diffraction to vastly improve the technology and set up they had at King’s and obtain better diffraction images of DNA than had ever been possible there before. She then started on the complex and laborious task of mathematically interpreting the data to infer the structure of DNA. Her understanding of chemistry combined with her high-quality experimental results meant she got most of the way to finding out the structure. She realised it must be a helical structure with the phosphate groups on the outside but had not figured out how many strands of DNA were in the helix and hence how the bases fitted together. Before she could get to the answer Watson and Crick beat her to it, a common phenomenon in science and not one that is usually that dramatic, but this time it was.

Franklin’s story is often told, not incorrectly, as one of sexism-fuelled injustice, but what this book does so beautifully is deepen and widen that story to one of a fiercely talented and driven scientist with a passion for adventure and discovery that spilled over into her life outside science. Although she died from ovarian cancer at the age of just 37, she published 45 papers across three different fields of research (structural work on coal, DNA and viral RNA). This would be an incredible feat for a male scientist who lived to old age, but she accomplished all her achievements over just 15 years, all the while battling sexism from all angles. It affected concrete things like her pay and her ability to get funding for her research, but it also shaped how her colleagues viewed her and her work. The descriptions of her from colleagues who worked closely with her are generally glowing. Her student at King’s and the members of her group when she moved to Birkbeck had a deep respect for her talent and work ethic. She likewise cared deeply about them and battled for financial security for them and their work even whilst her health was declining.

One step further away however, from colleagues who worked near but not with Franklin, the descriptions are soaked in sexism. In his book ‘The Double Helix’ about the discovery of the structure of DNA, James Watson includes detailed criticism of her appearance and how she dressed. He also writes about how they patronisingly referred to her as Rosy because she didn’t like it and Crick acknowledges in hindsight that they had a patronising attitude towards her (driven by sexism perhaps? It’s impossible to tell…). She is regularly described as being blunt and stubborn in a way that made her hard to work with. All I could think when reading these criticisms was: how could a woman in that time possibly get anything done in that world without being blunt, stubborn and incredibly determined? Sexism has shaped how she is remembered in these anecdotes, not only because working in such a sexist environment necessitated and drove pig-headed and defensive behaviour from her, but also because that behaviour by a woman was unforgivable in a way that would never have happened with a man. On top of that, the way those criticisms are used to justify the use of her data by Watson and Crick without her consent and the complete lack of recognition for her work on DNA is a continuation of that sexism. Watson and Crick were especially motivated to downplay the importance of her work as the basis for theirs, given that they saw her data without her knowledge or consent, and their narrative worked.

The section on Franklin’s Wikipedia page that addresses sexism is headed “alleged sexism” and lists examples of ‘potentially’ sexist things that were done/said about her followed by reasons why they weren’t that bad or weren’t actually sexist. One of which is that Franklin herself wasn’t a feminist, said sexist things and would’ve been embarrassed by this interpretation of her career (not that that last point can ever be confirmed). The idea that just because someone has also internalised the sexism of their time and is therefore sexist themselves means that they can’t be subject to sexism is completely illogical, but this narrative on Wikipedia is a brilliant example of how sexist attitudes to Franklin and women in science generally continue to this day and why the scale of the injustice towards Franklin is still relatively unknown. In this section they misuse quotes from Maddox’s book to imply that she didn’t think Franklin was treated in a sexist way which, if you read the book you will find is most definitely not the case. Maddox’s book is not an on-the-nose feminist rant, but actually quite a nuanced, balanced account of Franklin’s life with the main goal of allowing the reader to understand her. Despite this mild approach, the sexism Franklin faced throughout her career is glaringly obvious – the events speak for themselves.

I strongly recommend this book as a detailed and entertaining account of Franklin’s life and career as well as the story of the discovery of the structure of that all important molecule, DNA. Reading about Franklin’s attitude to her research and her life inspired and motivated me in my attitude to my own.