For the first in my blog series: Exploring the science behind everyday plants, it seems appropriate to cover Roses.

The name “Rose” refers to over 300 species of plant in the genus Rosa. They can range from miniature garden roses to climbers that can reach well over 7 M height but one thing they all have in common is the showy flowers they produce.

Rose colours:

The colour of these flowers was used as a sort of language in Victorian England, each symbolising something different. White was for innocence and young love (hence why white roses are common in bridal bouquets), red was for romantic love, yellow was for jealousy and pink was for friendship. Of course, there are thousands of cultivators with mixed colours these days so, in theory, you could send a very nuanced message if you wanted to!

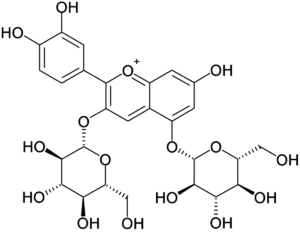

The chemistry behind the colour of roses is pretty cool. Cyanidin-3, 5-O-diglucoside, an anthocyanin, is principally responsible for reddish tones. The diglycosylation is performed by a single glucosyltransferase and occurs at the 5-OH position before the 3-OH position. This is unlike other plants, which usually only show glycosylation at the 3-OH group. The colour yellow is produced as a result of carotenoids- over 75 have been identified so far, some of which are also present in apples. In orange roses it is a combination of both of these groups that results in the colour, with the ratios of each leading to variations in the reddish/yellowish-ness. Contrastingly, white roses are perceived as such because the compounds they contain don’t absorb light in the 400-700 nM range. However they are not transparent- UV absorbing substances such as flavonol glycosides have been found to be present in large quantities and some colourless carotenoids have also been identified.

Science behind scent:

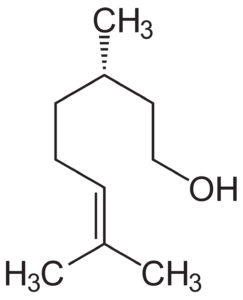

Roses are usually well known for their scent, with Damask Rose perfume being particularly valued. The scent is principally a result of (S)- Citronellol, geraniol/nerol (these are E/Z isomers of each other) and β-ionone. However not all roses are scented, especially garden cultivators, as non-scented roses tend to stay fresher for longer. In 2015 the gene responsible for the scent of roses was identified as RhNUDX1. Knocking this out in the petals of roses known for being scented resulted in almost no scent being produced. Now that this has been identified it offers the possibility that scent can be bred back into new cultivators which may also prove advantageous for attracting pollinators.

Can I eat the fruit?

Something many people don’t realise is that the fruit of the rose, the rosehip, is edible and actually quite tasty. All roses produce rosehips but the ones you’re most likely to be familiar with are those from Rosa canina, the Dog Rose, that grows wild as a shrub in the British countryside. You can eat the fruit raw, but the inside has fine hairs that can irritate the throat (in fact these used to be used as itching powder!) so instead it is best cooked down into syrups and jellies or used in herbal teas. Rosehips are rich in vitamin C but, contrary to popular thought, the claim that they can help with arthritis and other inflammatory issues has yet to get any scientific backing.

Random history fact:

Of course I couldn’t do this post without mentioning the War of the Roses. The white rose was the badge used by those loyal to Richard of York (and subsequently Edward of York) as the York family attempted to take the crown in the mid-1400s. They were briefly victorious, holding the throne from 1471-1483 but in 1485, at the Battle of Bosworth, Richard III was killed and Henry Tudor declared King. He married Elizabeth of York, uniting the two houses to form the Tudor dynasty and merging the two badges to create the Tudor Rose, which is both red and white. These days you can actually buy roses that attempt to emulate the patterning of the Tudor rose although results do vary!