Somehow it’s March again and, with the unseasonably warm weather, many flowers are already making an appearance. One of my personal favourites are daffodils, with their bright flowers bringing some colour to early spring.

The Latin name for this genus is Narcissus and it’s often linked to the Greek myth of the youth falling in love with his own reflection. It’s said that the nodding flowers represent him staring into the pool. However, there is no evidence that this was the original intention of the name, with Pliny writing that it was in fact derived from “narkao”- I grow numb, in reference to the intoxicating fragrance of some of the Greek species. In the modern world these plants are mostly used for decorative purposes, but they have a few chemical surprises up their sleeves!

Do not eat the fake onions!

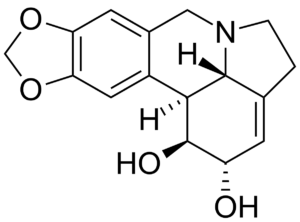

Firstly, the words of warning, if you plant daffodil bulbs in your garden make sure you don’t plant them anywhere near an onion patch. The bulbs can easily be mistaken for onions and the results will not be pleasant. They contain oxalates which bind to minerals in the body, particularly calcium, potentially causing kidney stones. Quite apart from that, you’d be very ill from lycorine poisoning. This alkaloid is not unique to daffodils, being found in snowdrops and bush lilies too, and causes unpleasant symptoms of vomiting, diarrhoea and convulsions. There is no definitive knowledge of how it works but initial investigations have suggested it may inhibit protein synthesis and acetylcholinesterase. Some studies have been conducted to look at it and its derivatives as potential anticancer drugs. By targeting the actin cytoskeleton, it doesn’t kill cancer cells outright but has cytostatic effects that prevent further growth.

But can we actually use them for anything?

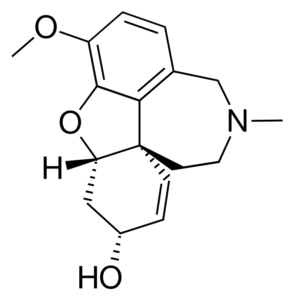

On a less poisonous note, another alkaloid, galantamine, has been developed into a successful Alzheimer’s treatment. It was first studied in the Soviet Union and later isolated from the common snowdrop by Bulgarian chemist Dimitar Paskov but, as with lycorine, it can also be extracted from daffodils. It acts as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor so increases the availability of acetylcholine for synaptic transmission. Additionally, it can bind to allosteric sites of nicotine receptors, modulating their response to acetylcholine. This dual action combats the impairment of cholinergic function that is characteristic of the disease. It also means it has potential as a treatment for organophosphate poisoning, something the US army currently has a patent out for. However, the synthesis of galantamine is complicated and without any studies on the biosynthetic route to allow the development of industrial scale biocatalytic processes, it is often still harvested from natural sources. Yields from this are low, as little as 0.1% of the contents of the plant.

It’s not all about science

With such a broad natural territory, daffodils have also had a huge cultural impact. They are the national flower of Wales and often associated with the season of Lent due to their spring flowering. Images of daffodils can be found decorating ancient Egyptian tombs and, in Islamic culture, they are said to represent eyes in many famous poet’s works. In English speaking countries today several cancer charities use them as fundraising symbols. Whatever daffodils mean to you I hope you can get outside and enjoy their beautiful flowers this month!